The Opium War by Julia Lovell

Review by Anna Chen – 17 May 2012

The nationalist not only does not disapprove of atrocities committed by his own side, but he has a remarkable capacity for not even hearing about them.

George Orwell

With renewed calls for the West to assert its imperial might in the interest of “capitalism and democracy … if necessary by military force ” (historian and BBC Reith Lecturer Niall Ferguson), it’s useful to examine one episode in Britain’s history when we attempted to do so, with catastrophic results for the conquered nation.

Britain’s craving for chinoiserie in the 18th and 19th centuries resulted in a trade imbalance which threatened to empty the treasury. In order to pay for the tea, silks, spices and porcelain we liked so much, the East India Company mass-produced enormous quantities of cheap Bengal-grown opium and, along with other British merchants, sold it on to China, turning an aristocratic vice into a nationwide addiction.

The profits from the opium trade made fortunes, earned revenues for the British government, paid for the administration of the Empire in India and even financed a large slice of the cost of the Royal Navy. In 1839, when the Chinese tried to enforce their own laws and halt drug imports, the narco-capitalists persuaded Foreign Secretary Palmerston and Lord Melbourne’s government to go to war in order to protect their profits. The first military conflict — thanks to superior technology, more a series of massacres — lasting a bloody three years, resulted in the Treaty of Nanking and the transfer of territory including Hong Kong to British rule. In waging the second war (1856-60) the British finally achieved their goal of seeing opium legalised in China.

That the Chinese government might use this notoriously brutal example of British imperialism to bolster their power is little surprise. That western authors now seek to diminish British culpability and shift responsibility onto the nation that suffered the predations of drugs and war is disturbing, though probably inevitable in the febrile current atmosphere of the China-bashing seen by many western intellectuals as a substitute for informed criticism.

The latest in a string of histories reviving positive images of Empire, Julia Lovell’s The Opium War is on a mission to reassess history, presumably seeking to replicate her literary stablemate Jung Chang’s success with Mao: The Untold Story.

A revisionist thread

Lovell’s argument hangs by the revisionist thread that, far from creating a market for opium, the British were only satisfying what was already there. “What had happened,” she asks, “in those four decades [to 1840], to transform opium-smoking from an acceptable displacement activity for an idle emperor-in-training to a perilous scourge?” Not British traders — who were only exploiting an existing weakness, it seems — but the Chinese themselves who were gagging for it and therefore the authors of their own doom. The point that opium was an expensive luxury until the British were able to mass-produce it cheaply in India and transform the market, is buried in a welter of smoke and mirrors.

Lovell sets out to correct the Chinese government’s overplayed narrative of victimhood but overbalances into a 400-page vilification of the Chinese: theirs is a response to a Western threat “supposedly” determined to contain it (“supposedly” is wide open to argument); the 150th anniversary of the first Opium War “offered a public relations gift to the government”; it is a “founding myth”, a mere “border provocation”. Opium is a “scapegoat” for the emperor’s problems, those who opposed it “ambitious moralizers” and “ambitious literati”.

The Chinese are capable of only the basest motives in their efforts to wipe out the drug that is crippling the nation, their emotional and behavioural range running the Sax Rohmer gamut of dehumanising tropes: stupid, arrogant, cowardly, lazy and pragmatic. “Perhaps they objected for Confucian, humanitarian reasons; or then again, out of indolence, maybe.” Their avowed repulsion and fear of what opium can do is dismissed, individual suffering skated over and characters never humanised. I’m not sure I detected any irony in her use of that old colonialist favourite, “wily”, and the drooling pages of lurid descriptions in the Yellow Peril chapter might have made room for the moving contemporary accounts of the destruction of the Summer Palace, for example, or the massacres of the Chinese which shocked even hardened British soldiers.

Double standards

In contrast, although some of the inescapable truths about the British drug-dealers and perpetrators of war are acknowledged, their actions are ascribed to human feelings; they are “generous”; their inner lives are explored; their flaws are treated with understanding for they are men on a quest to better themselves against a monstrous Empire that will not give them what they want.

When the moral high ground runs out, equivalence is strained: it was “mutual incomprehension that pushed both sides towards war”. “Contemporary China’s line on opium transforms it into a moral poison forced on helpless Chinese innocents by wicked aliens. The reality was more troublingly collusive.” Both were as bad as each other. When everyone is guilty, no one can be innocent.

The book’s selectivity is irritating, ultimately undermining the story. The British who grew industrial levels of opium and sent the price plummeting, are “diligent”, their supply benignly “reliable”. James Matheson is described kindly as a “tough Scot” and “living under the influence of the holy spirit”, but whose banishment to the wilds of Canada of 500 residents of the Isle of Lewis — which he bought and decorated with Stornoway Castle on his drug money — is overlooked in this hefty tome. Of Charles Elliot, Chief Superintendent of British Trade in China, one of the architects of the first Opium War and later first administrator of Hong Kong, she writes sympathetically that he ” … instinctively disliked the opium trade and everything bound up with it: both its moral dubiousness and its ungentlemanly profit-hungry merchants”. Sentimentally, “his weakness was to see a little of everyone’s side: he understood the economic imperative of the opium trade, even while he hated the vulgarity of its perpetrators; he understood that his duty was to protect the British flag in Canton, even while he detested what some of Britannia’s children were doing in the China seas.”

Commissioner General Lin Zexu, who destroyed 20,000 cases (each holding 140 pounds) of British opium in 1839, is presented as a bureaucrat (Niall Ferguson couldn’t even bring himself to name him in his account), albeit an incorruptible one, caught between a rock and a hard place. Lovell complains that “History has been kind to Lin Zexu”, although it’s not difficult to see why such an incorruptible force who tried to right an injustice might be a much-needed inspiration today. Her extensive research does, however, unearth the little gem that, once Elliot had finally handed over the opium stash, Lin made a gift to him of prized roebuck meat before which he “was careful to kowtow nine times”.

Rebranding the British Empire

There are some asinine reductions: “The Ming Dynasty was brought down in 1644 by insurrections led by a postman who happened also to be a failed candidate.” (Note the snobbery — how would a carpenter fare in her scheme of things?) The Taiping Rebellion with all its fascinating complexity and humane objectives (the abolition of landlordism, the redistribution of wealth for all, and the prohibition of prostitution, bound feet and the smoking of opium) is reduced to a nervous breakdown of a “provincial schoolmaster” — a movement crushed, incidentally, with the aid of the British acting in concert with the Manchu imperial army during the Opium Wars, a fact missing here, at a cost of 20 million lives over 14 years.

It’s not as if the Chinese need any lessons in the part played by the rotten Qing Empire in the nation’s downfall. The “disorganisation and cowardice of its own officials and armies” is already well known. There was indeed much “self-blame”, “self-pity” and outright “self-loathing” during and after the conflict which is still going on, as documented ad infinitum in China, with local militias fighting where Qing armies feared to tread, such as at Sanyuanli in 1841 (also derided by the author). It was the corruption of the old empire which led to its fall in 1911 and the establishment of a republic under Sun Yatsen, and which added grist to the communist mill in trying to stamp out the remnants of the old system described so luridly by Lovell.

Reading her account is a bit like hearing a rapist declaring his innocence because his victim wore a short skirt as she walked up a dark alley. Not only were there an estimated 120 million addicts in China at the trade’s peak, but national treasures were looted or destroyed, and massacres and rape perpetrated by the invading troops intent on forcing the drug on the nation. So bad was this savagery that large swathes of British public opinion clamoured against the opium-driven conflict, led by the voices of such as Richard Cobden, William Gladstone and the Chartists. But Chinese outrage is ridiculed, with no room for the possibility that they might authentically feel empathy and concern or be justified in their anger. While paying lip service to some acceptance that a crime had been committed, Lovell offsets the gravity of the injury with a running national character assassination and a downplaying of facts already known and documented.

It’s difficult to relax into the rollicking story that’s fighting to get out as you are constantly poked in the ear with the author’s “they made us do it” mantra. Lovell is much stronger when she tells the story straight and without pro-imperialist spin, but it is largely marred by an unfortunate sneering tone which plays to a gallery of prejudice and jingoism, a Great Wall that will keep out any reader whose bigotry is not being fed. This is a shame because she has done a formidable job by laying out the story in so much riveting detail.

However, far from presenting a brave new take on the history, this is an old dish reheated, a rebranding of Empire (do we still call it the Indian “Mutiny”?). Lovell replays the excuses made in Britain at the time by the narco-capitalists and Lord Palmerston, who tried to win over a public opinion revolted by the idea of a narcotics war by playing the insult to the flag by the Chinese and the “liberating values of Free Trade” cards. To this she adds a steady poisonous drip of various distancing devices and systematic “othering” of the Chinese.

Dehumanised

The narrative spin dehumanises the Chinese, divesting them of moral capacity while painting violent drug dealers as acting out of a higher calling, themselves passive victims of force majeur. Hence, while Elliott considers opium smuggling to be “a trade which every friend of humanity must deplore”, he wants the Qing to “legalise it, because it would force the Chinese to take full responsibility for its moral dubiousness”, the opium trade being the fault of the addicts and not the suppliers. Elliot has a “conscience” while Lin is merely a bureaucrat who is described from the outside in, a bundle of facts with no heart. Elliot possesses an interior landscape. His “weakness was to see a little of everyone’s side”. He “understood his duty was to defend the British flag in Canton” even though he “detested” what his compatriots were doing. Yet, like Lewis Carroll’s Walrus, he weeps into his handkerchief over the plight of the poor oysters while scoffing the biggest ones himself when he lands the British government with the inflated £2 million bill for the confiscated opium and thereby hands them the final excuse for war.

The rest of the book similarly struggles with balance in a scattergun outpouring of distaste for nearly everything and everyone Chinese. Lovell’s account of the breakdown of the Copenhagen climate summit in 2009 is ludicrously one-sided — she makes it appear that it was all China’s fault, with no mention of the Danish Text stitch-up of the talks by the wealthy nations — and she has nothing to say about China’s massive efforts to cut carbon emissions and combat pollution. She condemns Chinese anti-Japanese hysteria but never mentions former Prime Minister Koizumi’s provocative visits to shrines of war criminals and rewritten history books. Sun Yatsen is a “chancer” who was snubbed by the head of state and that’s why he brought down the Qing. Bored students obsess about their careers. Interviewees interrupt their “self-loathing” denunciations of the West with requests for job-tips and enquiries about how to get on in the land of the rising shun. Chinese don’t need to indulge in self-loathing while Lovell’s on the case because she can loathe for England. By the end, you are willing the poor woman to retrain in another field altogether just so she can find some peace of mind.

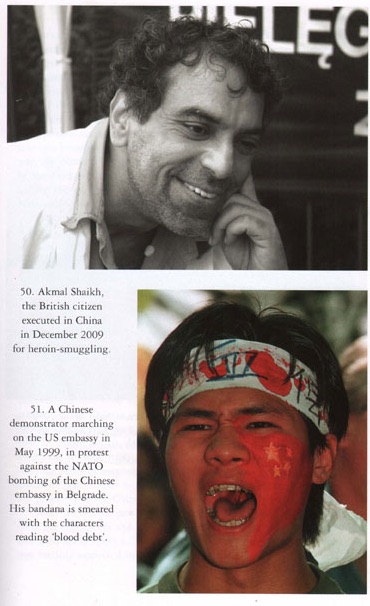

Perhaps it’s the illustrations which tell the story best. A photograph of Akmal Shaikh, the Briton executed in China in 2009 for smuggling heroin, is juxtaposed favourably with one of an emotional protester following the US bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in 1999, killing three journalists — an outrage claimed by the US as an accident even though the allies had the map co-ordinates and knew where the embassy was. Those of us opposed to the death penalty argued that a prison sentence was a more humane and apt option for Shaikh, especially if he was ill as claimed. But if one picture is worth a thousand words, then the juxtaposition of these two photographs speaks volumes. The British smuggler of 4 kg of heroin into China is portrayed with sympathy while the other is not. It is a deeply flattering, almost saintly, portrait revealing the humanity of the drug-dealer, set against the ape-like rictus of the Chinese protester in the grip of a feral rage. One is humanised, the other dehumanised. One life has value, the three dead and 20 injured Chinese do not even warrant a mention anywhere. This twisted morality evoking a visceral response — empathy for us and revulsion for “them” — as employed in the use of the photographs, permeates the book.

Lovell seeks to make a case against the communist government, but her thrust replaces one orthodoxy with another. In describing the fundamental rottenness of an ossified and decadent empire (China’s, not ours) she inadvertently stirs a degree of sympathy with those men and women who tried to build a better society in response to the horrors visited upon a country on its knees but who have tragically failed to avoid writing their own catalogue of misery despite doubling life-expectancy and raising 600 million out of absolute poverty. As a demolition job on the upstart rival on the global stage, this book is sure to do well among those less scholarly than the professor who will seize on this exercise in exculpation with glee.

Anna Chen wrote and narrates The Steampunk Opium Wars.

Niall Ferguson dismisses the Opium War

At last, someone else has done a thorough analysis of The Opium War here at Hidden Harmonies.

Excellent piece – makes me want to read the book!

Excellent review!!

I lurve Lovell"s view re "all bad as each other" as it is such an almighty cop-out and a total abdication of thought and analysis. But that's right-wing revision for you!!

She didn't actually use those words and there's lots of thought in there but it seems to be in service to an agenda that I find quite horrible. It certainly is a revision, though, and, from where I'm standing, looks pretty right wing.

After reading your review of this book I was intrigued to see how it had been reviewed elsewhere. I read the reviews at The Indy and the Guardian which are both, basically, unquestioning explanations of the opium wars, presumably just abridged versions of the book – hardly enlightening and they certainly don't critique the book in any meaningful way. One would have hoped for more from a professor at SOAS and a supposed expert on China.

However, thankfully there was Madam Miaow to redress the balance a bit! Thanks for a great, and informative, review.

Excellent review!! I lurve Lovell's "all as bad as one another" as it is such an almighty cop-out along with a total abdication of thought and analysis. But what can you expect from a right-wing revisionist and apologist for British imperialism….

I felt a certain sense of uneasiness after reading the first 15 pages. By the time i got to the end of a hundred, i was keen to read a critical review. Yours was the only one i came across and i'm grateful since it affirms the sentiments i was feeling. It's a paean to Empire, certainly an attempt to absolve Britain's culpability in state-sanctioned brutality and murder. It is racist and takes a completely amoral stance – the very posture required by pro-empire types. Lovell is not unlike a Niall Ferguson – how could anyone be so Brutish, one might ask – perhaps a tad more subtle. Thanks for your review. It deserves to be widely read. Ever considered publishing it in academic circles?

best wishes

Thank you, Ty. The absence of analytical criticism of this book was most disappointing. Academia and media asleep at the wheel.

Thanks, Madam Miaow.

Irritated by her subtle but resolute defence of the British empire, I looked online for Julia Lovell

and was shocked by the tremendous awe caused by the Opium War:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Zb-aecx4xQ

As you'll see, she was feted in HK at the launch of her book.

But that is not all. The moderator at the launch, a bloke called Chip (not sure if he's just a potato chip or a French Fry) is an even greater apologist for British empire!

At the end of the talk he tells her that "as beneficiaries of the Opium War" (he seems quite presumptuous about his self-conferred right to speak for others), he would like her to return to Britain to convey to the British people how grateful "we are", and that "we" feel sentimental about the times pre-1997 .

At some point in the talk, he even tells Julia Lovell to dispense with any guilt she might have still harboured about Britain's culpability in the Opium War.

Its incredible and painful to watch, the self-loathing and sycophancy.

Back to Julia: when asked about 'unequal' treaties (around the 1hr 11min mark), she remarks something to the effect that although they represent a loss of political and economic sovereignty, these treaty ports actually became hubs for practices and freedoms of all sorts i.e. centres of political, cultural, economic vibrancy.

See how subtly these pro-imperialists make their case? They completely side-step the moral question of the British imperialist enterprise by referring, retroactively, to its (incidental) 'positive' consequences. It's a little like absolving a rapist post-hoc when the child produced from his act of depravity turns out to be a genius.

In this amoral scheme, the ends ('civilization') are absolute and so they justify the means, whatever their costs. There is complete amorality.

Obviously, what seems to be sadder than the perfidious colonial apologetics of the likes of Lovell is the subscription to such ideology by the very subjects – the 'victims' – of empire. This is quite evident from the clip, with virtually every comment from the audience expressing views supportive of Lovell's, seemingly oblivious to its racism and pernicious implications.

Where is Fanon, Nandy, Memmi or Cesaire when one needs them? It's almost as if the colonized have been so deformed by their colonization they can't recognise the phenomena even when it lands on their faces!

Again, I'd urge you to consider publishing your review more widely.

Oh, dear lord. That video is tragic, Ty. However, there are forelock-tugging house-slaves everywhere and always will be. All we can do is marvel and blow raspberries whenever they embarrass themselves like this. Re publishing my review more widely, I'm cheered by the fact that it will turn up in any online search for the book and people can make up their own minds based on the argument. Anyone who wishes to publish it in the interests of the debate is most welcome.

Wanted to commend J.Y Wong's comprehensively erudite treatment of the second Opium War:

Deadly Dreams and the Arrow War (1956-60) in China. He's also fittingly written a review of Lovell's book, generously suggesting that it was her 'mistakes' that put her 'in grave danger of being an apologist for British imperialism.'

Excellent review!! I lurve Lovell's "all as bad as one another" as it is such an almighty cop-out along with a total abdication of thought and analysis. But what can you expect from a right-wing revisionist and apologist for British imperialism….

It's several years after the fact, but as someone who recently read the book and found it interesting, I wanted to thank you for writing this critique – there's scarcely any, and that's a sad state of being for any acclaimed book.

I just wanted to ask you the question, is the book at least right as far as the historical details go – stuff like the silver shortage leading to unrest or the emperor repeatedly sacking his commisioners for their failure in dealing with the english?

Fantastic Work, Anna